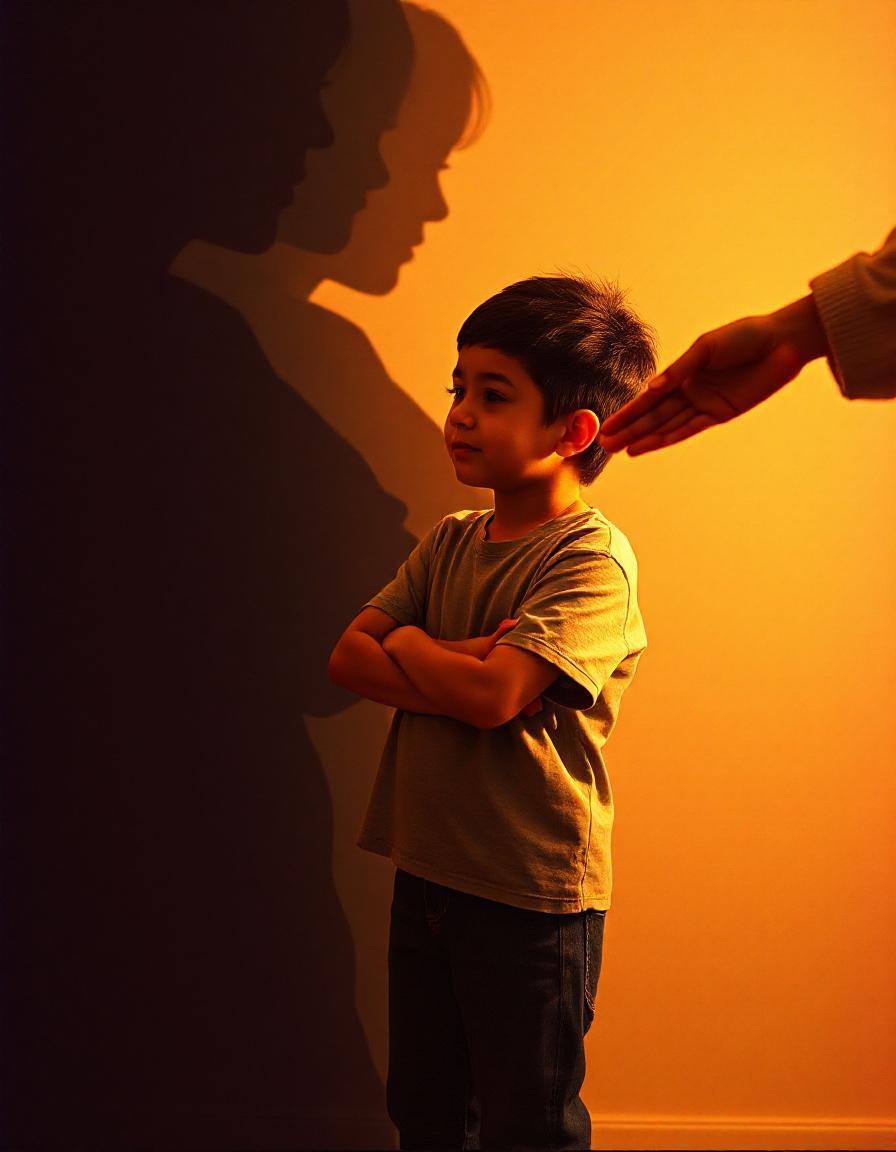

It is perplexing to understand why children with a difficult past that often includes instability, neglect and perhaps even abuse, would not desire and do all they can to find comfort and support. Many foster and adopted children do just that. They understand and value safety and caring parents, and some of these children just can’t get enough after difficult early years of life. But this is not true for all foster/adoptive children, and this article will focus on those children who seem to work against their own best interests by pushing caring parents away.

We must start this topic by saying that as adults we cannot be too quick to say what the greatest needs are for these children, because our list may be very different than the child’s list. Where we see safety and comfort, these children might see vulnerability and pain. For these children even when times are good, they wonder how long the good times will last and losing something great may be worse than never having it at all. To make this point, perhaps it will help to reflect back on an early love interest in our lives. There is nothing quite like making a new friend and finding how special it is to love someone. However, seldom is our first love someone who becomes our life-long partner, and this is actually a good thing in the long run. However, try telling that to the young person who is grieving the loss of a first love. At such a time we experience the vulnerability and hurt that comes with investing in a relationship that ends. This is the vulnerability that many foster and adopted children avoid at all cost.

Research shows that our emotional state is a combination of our genetic disposition, our life experiences and our free choice. If we wonder why our foster child is in a consistent bad mood, consider these elements. How many adopted children had wonderful early years of life with a strong bond with parents? And how many went through early years of childhood with the love, nurturing and stability they needed? If the child comes into your home with a painful past, we must consider the third element that makes up our emotional disposition–our choices. Are we surprised that a hurt child would prefer not to be hurt again?

All parents doing their best to raise a non-biological child realize that understanding the child’s past history is critically important. But how well do we do at this? Some children have very few records, in fact the children who have struggled the most in biological families often have the least historical information available. Even when there are records of removal from the home, parental involvement in substance abuse or illegal behavior, there is always much more to the story than is documented. The rest of the story is the internal impact of the damage to the young child. It may make perfect sense to you that the young person would now want to reach out to you or at least respond to your love and caring, but ask yourself if this makes sense to the child?

The quick answer to the opening question of why foster/adoptive children push parents away can be stated in one word—vulnerability. Often even more than safety, the most vulnerable a person can feel in life has to do with love and the potential for hurt. There are many individuals who test the limits of safety—firefighters, soldiers, mountain climbers, snake handlers and race car drivers among others. But even these individuals would generally prefer their physical risk to the emotional risk of losing love in their lives. We talk about the highs and lows of loving another person, but to foster and adopted children this is not about romantic poetry, this is emotional survival. Many of these children will not reach out even if it appears that it is a sure thing, because they know from experience there are no sure things in life. For most of these children, being lonely and alone is preferable to being hurt or risking more loss. The solution is plain and simple—keep others at a distance particularly those who come on to you and offer love and caring or so they pretend.

Our brains are programmed to promote our survival. Linked to this is the brain’s programming to promote thriving in life. For example, a healthy individual will seek pleasure over pain if all things are equal. But the brain can be re-programed, and the most potent re-programmer is trauma. Experiences that override our ability to cope (the definition of trauma) can have profound influences on the programming of our brain. For example, after trauma some children pursue pain and avoid pleasure, they ignore safety and embrace serious risk, and they override their own emotional needs and isolate themselves. And if one of these children is in your home, your relationship with such a child can seem like swimming against a strong current—despite all the effort it is still hard to get where you want to go.

If all this sounds like an impossible or at least a very difficult task, the point is not to discourage you but instead to offer ideas to improve your odds of success. The first step is to understand the plight of the child, not understand it intellectually but on a deep emotional level—which is where the child feels the risk. For most adults an intellectual understanding allows them to consider where the child is coming from with some emotional distance. However, when in the thick of things and with emotions run high, this level of understanding can go out the window and we all revert to more primitive self-protections such as blaming the child, withdrawing our caring and even emotionally striking back. If the child experiences any of these responses it will confirm your love and caring are only surface deep and therefore not real.

It is important to briefly discuss how foster/adoptive children test new parents and others who care for them. Testing comes naturally to these children. You should first realize that if a child tests you in a significant way, this can put you in a difficult spot, but is actually a good sign. Children who have experienced trauma do not easily test adults they consider to be a safety risk. If the child confronts you verbally or even physically, part of the message is a belief that you are safe enough not to retaliate. Another reason testing is a good sign is it gives you a chance to show the young person that you and your love are for real. You cannot tell them with words that your caring is real, you must show them by your actions. Testing a parent is the key to disconfirming the young person’s belief that you are like all the other adults who have been disappointments. Here is where deeply understanding the child plays out, when you are being tested consider this a positive opportunity for your relationship with the child and not react to the content or the rude way the testing is delivered. Testing must be difficult or why would it be helpful? There is one central understanding of all testing by these children—despite what they do and what they say, they want you to pass the test.

Another way to deeply understand the emotional state of the child is to understand that love (a basic need) must be experienced within a bond or attachment to an adult. There are four keys to working toward forming a bond with a foster/adoptive child who keeps you at a distance:

- Provide a safe environment – We must start with safety because there is no healing and little positive personal growth that can happen when the environment is unsafe. But we must take it a step further, whether the situation is safe is not for you to decide but for the young person. Even in a safe situation, if the child perceives being either physically or emotionally unsafe this first step is not accomplished. All trauma is individual and internal. Once again this requires us to climb inside the world of the young person to ensure the experience of safety.

- All basic needs must be unconditionally met – For this second step we need to broaden basic needs to be more than food, shelter and clothing to also include needs that are seldom considered basic: stability, belonging, touch, healing, self-expression, opportunities to learn, self-determination, joy and love. The important word here is unconditional, the young person cannot have basic needs withdrawn by poor behavior or disrespect. If so, how does the child know that other basic needs will not be conditional as well.

- Consistent invitations to connect must be extended to the young person – A standard behavior from troubled and anxious foster/adopted young people is keep you at a distance (the topic of this article). It is essential that all efforts to keep you distant, have you give up, and to physically or emotionally distance yourself cannot be successful or both you and your foster/adopted child lose. Even when it is difficult (especially when it is difficult) you must continue to reach out and invite the young person to connect with you. Even if you have little hope for a truly close relationship, then do it anyway for the young person’s future.

- All wants of the child (not needs) must be connected to reciprocity – This last step can be difficult for many adults, but it is where either success or heartache are found. Relationships can never be one way, therefore reciprocity is essential. But how do you establish a two-way street with someone who only thinks of him or herself? The answer is reciprocity training or what has been called in the past “tough love.” Reciprocity is not something you merely ask for, you must require it. You cannot demand caring and affection, but you can expect the young person to return something in response to you meeting their wants (not needs). Make it clear that needs are never conditional, however wants are always based on what they will do to

get what they want. Many parents find this unpleasant and even demanding, and yes it is demanding in that it forces the young person to understand that relationships go both ways and involve more than one person’s wants.

It is a good idea to change your focus from what behavior you want from your foster/adoptive child to what steps you can take to improve your mutual connection. Our job stated briefly is to change the young person’s experience of a relationship with an adult. Most young people who have been removed from their biological parents have had a rough time with adults—they may have been abused or neglected, adults make all the decisions and they have no voice, and many have been in many placements without the time and ability to bond with anyone. We must change that if we want the young person to grow up in a world that includes positive relationships with others. If this child does not learn connection is good from you, then who will they learn it from?

Foster/adoptive children are all unique as are all parents. The key to successful parenting and forming connections to reluctant young people is to disconfirm the child’s past and provide the child’s higher order thoughtful brain the experience that life can be richer and more successful allowing others into their world. How you use your unique personality and talents will require your creativity as well as your persistence. What can be in your favor is your consistency and the stability of your home environment. Most foster/adoptive children have not found many consistent parents, at least consistent in positive ways. Time is on your side, so pace yourself and work for the long-term and not expect major successes before the end of the month. In one important way your efforts to form a mutually beneficial bond with a child is setting the stage for relationships in the future, with friends, partners and children of their own. So even if you do not taste the fruit of your efforts, your work has not been in vein.

Finally, we know that young people best learn not from our words but from our actions and our modeling. There is one essential element these children need to learn from us and that is vulnerability. Most traumatized young people would rather be alone, unhappy and even in pain than to be vulnerable. For these children there is just too much to lose so they protect themselves, even from you. It is difficult for a parent to reach out over and over and get rejected each time—this is never easy. Does that make us vulnerable—absolutely, and that is the point. What better way to model vulnerability than to face a child who pushes you away and reach out anyway. Remember that most of the time children who test adults by pushing them away, secretly hope the adult passes the test, and does not give up and believe it is hopeless. It is not hopeless unless we do give up. Every adult who allows a troubled young person to push them away actually confirms the child’s experience that adults don’t really care despite what they say. Your mission impossible (if you choose to accept it) is to disconfirm the young person’s past experiences, practice the four steps outlined above and invest in a connection and hopefully a relationship at some point. Even if you plant a seed of what a true relationship is, it may not be you who reaps the harvest but someone else. But consider that your efforts may just change the young person‘s life and in the process it can change your life as well.